Scroll anywhere on BookTok or Bookstagram and you’ll see Canva-decorated lists of “Weird Girl Lit” or “Weird and Unhinged” book recommendations, including from your’s truly. At World Con this year, there were at least five panels on weird books, several focusing on Latin American literature. But have you stopped to think about why “weird” is such a trend right now? How has weird fiction evolved from the pioneers of the speculative fiction genre to our weird present day? And finally, what makes a book “weird?”

Since I read a lot of books that are described as “weird” for my book discussion group, I think about weird books a lot. My library patrons love weird books and read them all the time. I’m also convinced that we are probably the only book club that has requested to read Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol and Bunny by Mona Awad in the same month. Which begs the question: how are we defining “weird” and are older “weird books” different from new ones?

The History of Weird

Going back to the origin of the phrase, “weird fiction” was a term used to describe speculative works in the late 19th and early 20th century. Edgar Allan Poe and Sheridan Le Fanu were two pioneers of this subgenre, though they did not have the term “weird fiction” at the time. Weird Tales, a pulp magazine, popularized the notion of “weird.” While H.P. Lovecraft’s harmful beliefs make it hard for me to give him credit, he also popularized the term in his writing. At the time, “weird fiction” meant science fiction or horror that plays with ambiguity and themes of the unknown, in opposition to romanticism and the Gothic. A pretty broad definition, right?

In the 1990s and early 2000s, an era of New Weird Fiction was born. This was popularized by authors riffing on genres and ideas presented in older works, such as Jeff VanderMeer and China Miéville. In this new iteration of “weird,” many authors were playing with the notion of traditional genre and form while also fiddling with Old Weird tales. New Weird Fiction meant postmodern speculative fiction often combining old and new themes, such as mythology and futurology. In other words, “New Weird Fiction” is as difficult to define as the term “postmodernism.” In Ann and Jeff Vandermeer’s The New Weird Anthology from 2008, the new weird movement was “already behind us” at the time of publication. So, what followed in its footsteps?

On BookTok and Bookstagram, I see a lot of titles written in the past decade highlighted as “weird books,” mostly by women and for women. These books aren’t so much playing with form or twisting genre into a shape that we’ve never seen before. They are playing with unlikeable characters and unreliable narrators to push back against the confines of character-driven literary fiction (though some toe the line). While women have been involved in the movement or declared as “weird” from Old Weird (Leonora Carrington, Anna Kavan) to New Weird (Kelly Link, Katherine Dunn), much of this genre has been dominated by male authors. The NEW new weird fiction is very girly and extremely online. With the way weird fiction is trending, I predict that fiction by playing with ideas of gender fluidity, body horror, technology and dystopia against a speculative backdrop will be the next iteration of weird lit. It’s already starting.

What is a Weird Book?

I opened this question up to the members of my book discussion group and we all had a different subjective definition of “a weird book.” Some said books that were “unconventional,” “challenging the norm,” “experimental,” or “genre-blending.” Others said it’s more of a feeling, like “books that make me raise an eyebrow.” The New Weird Anthology writers also weighed in on their definition of a weird book on a message board post initiated by M. John Harrison, where everyone seemed to have a different take (literary genre-fiction, grotesque fiction, fiction in opposition with modernism, genre fiction gone mainstream, to name just a few). My personal definition of a weird book is a book, usually speculative, that plays with genre and defies my expectations (which in itself is a subjective!). Basically, my and others’ definitions are unhelpful except when viewed as a whole, showing how subjective the term really is. I argue that this subjectivity makes the viral subgenre more appealing and apt for social media arguments and intrigue.

But are we using the term “weird” to perpetuate otherness in speculative fiction? A friend who attended World Con relayed a story to me about one of the weird book panels. At the panel, The Saint of Bright Doors by Vajra Chandrasekera was discussed. In the United States, publishers and readers find this book “weird” but in India and Sri Lanka, it is just fiction. There is an entire chapter in The New Weird Anthology about how many European editors do not see a difference between weird fiction and fiction (my favorite response being from Romanian editor Michael Haulica who writes “I don’t think there’s a difference between the Romanian approach and the New Weird. We are all writers in the same world. Sometimes a Weird World,” 353). However, speculative fiction often contains genres that attract readers and writers who feel outside of the publishing industry’s “standard,” so this is a real cause for concern. Are we calling diverse books “weird” solely because they’re often “own voices,” or are they also doing something new with form, content, genre, and character?

I can only speak from my perspective, but I don’t think see it being used as a negative device, at least not the majority of the time. Or at least to me, the term “weird” is not being used solely in an “othering” way but in a marketing way (which brings its own capitalistic baggage). In The New Weird Anthology, most of the writers agreed that the term is used by publishers to describe fantastic books otherwise not easily described. Slapping a “weird book” sticker is a marketing tactic, if anything: it’s clickbait that encourages reading. From the few authors that I follow on social media, they actually seem to relish that their work is labelled as “weird.” And while it feels a bit overdone online, so did New Weird Fiction wave in the early 00’s. Eventually we will get sick of this trend and it will lose its meaning. We will take a little break and come back even weirder.

To refer back to the above sentiment– all of our definitions of a “weird book” are powerless until they are put alongside each other to show really how diverse this subgenre can be. While we disagree on definitions, we can agree that weird books can be amazing. It’s a loose enough term that it can be applied to a variety of different books, and I see the term encouraging people to read books outside of one’s comfort zone. Weird books open new ways of thinking about literature, life, the world, and ourselves. Plus, the “weird” moniker creates a community of readers who feel a little misfit, so naturally, they flock together. Weird books are powerful, change-making community-building titles.

While I was writing this piece, a college-aged library patron came up to me to ask where to find The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov. I told her where to find it and we had an exchange about how she was reading it for a book club. I told her we read it for my book club and that it was weird (in a good way). “Weird as in Earthings-weird?” she asked. I would never put Earthlings author Sayata Muraka in the same category as Mikhail Bulgakov, but I love that younger Muraka readers are reading Bulgakov (and that readers of the classics are branching out into the contemporary) because of the moniker “weird.”

Weird Reading Recommendations

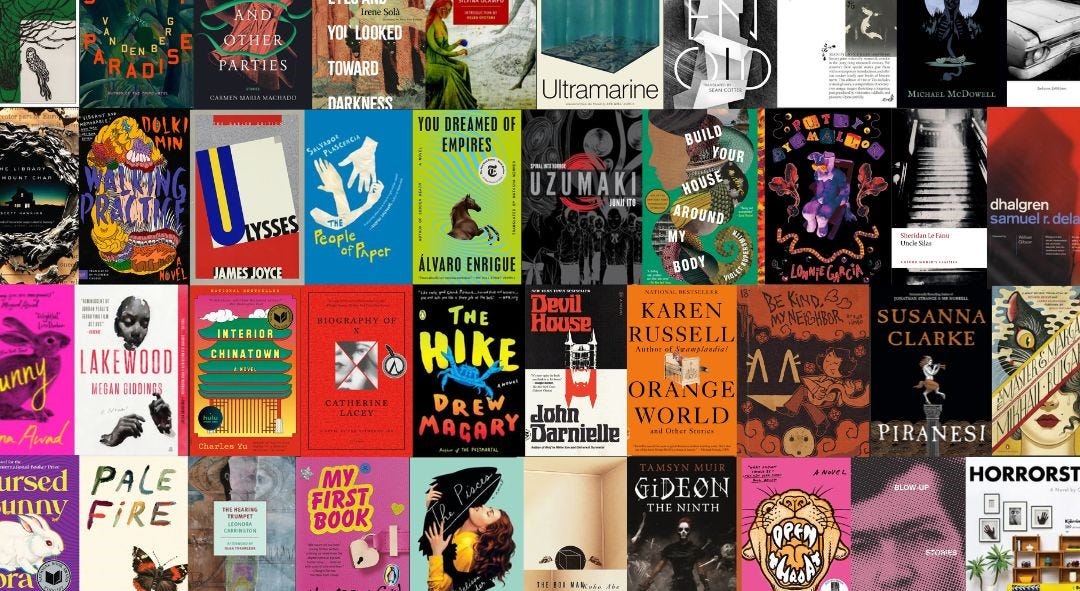

As we have established, “weird literature” is as subjective as calling things “scary” (to reference the title of this blog), but I thought I can’t write about weird fiction without throwing out some titles. I’ve read most of these titles and I also tried to limit myself to one book by each author and tried to recommend books that I don’t see a lot of on Bookstagram (though you’ll see some internet darlings too). Here are 100 books that I think totally deserve the “weird” designation, and believe me when I say that I could’ve added 100 more.

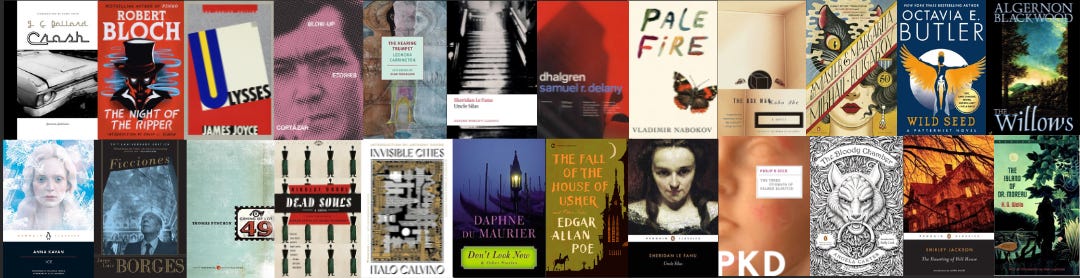

The Old Weird

- The Master & Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

- Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges

- The Box Man by Kobo Abe

- Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov

- The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

- Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino

- The Hearing Trumpet by Leonora Carrington

- Dhalgren by Samuel L. Delaney

- Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by M.R. James

- Wild Seed by Octavia Butler

- Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol

- Blow Up & Other Stories by Julio Cortazar

- Ice by Anna Kavan

- Ulysses by James Joyce

- Don’t Look Now and Other Stories by Daphne du Maurier

- The Night of the Ripper by Robert Bloch

- The Fall of the House of Usher by Edgar Allan Poe

- Uncle Silas by J. Sheridan LeFanu

- Blood and Guts in High School by Kathy Acker

- The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon

- The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldrich by Philip K. Dick

- The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter

- The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

- The Willows by Algernon Blackwood

- The Island of Dr. Moreau by H.G. Wells

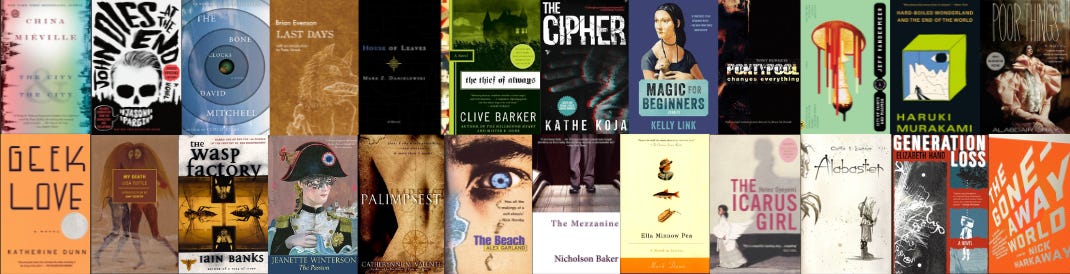

The New Weird Fiction

- The City & the City by China Miéville

- John Dies at the End by Jason Pargin

- The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell

- The Cipher by Kathe Koja

- The Wasp Factory by Iain Banks

- The Passion by Jeanette Winterson

- Palimpsest by Catherynne M. Valente

- The Beach by Alex Garland

- Pontypool Changes Everything by Tony Burgess

- The Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker

- Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn

- Hard-Boiled Wonderland at the End of the World by Haruki Murakami

- The Icarus Girl Helen Oyeyemi

- My Death by Lisa Tuttle

- Alabaster by Caitlin R. Kiernan

- Generation Loss by Elizabeth Hand

- The Gone-Away World by Nick Harkaway

- House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski

- Poor Things by Alasdair Gray

- Geek Love by Katherine Dunn

- Last Days by Brian Evenson

- Magic for Beginners by Kelly Link

- City of Saints & Madmen by Jeff Vandermeer

- Cold Moon Over Babylon by Michael McDowell

- The Thief of Always by Clive Barker

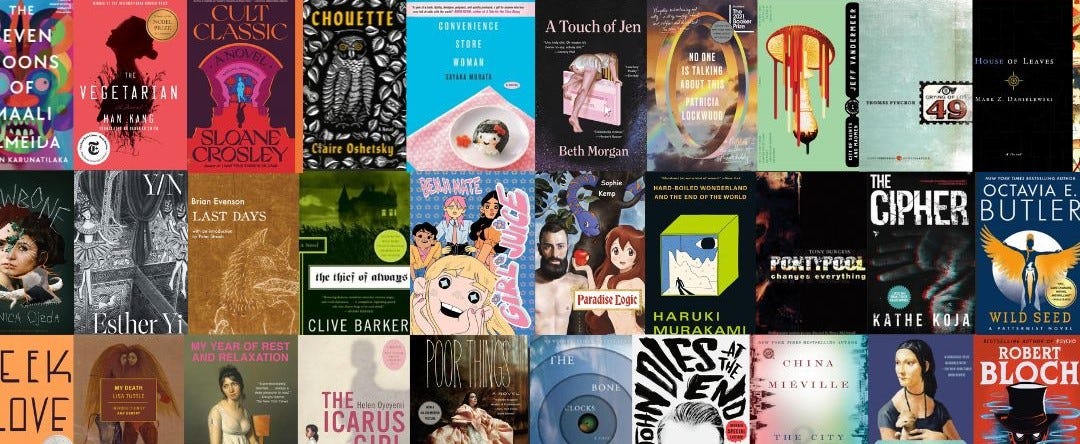

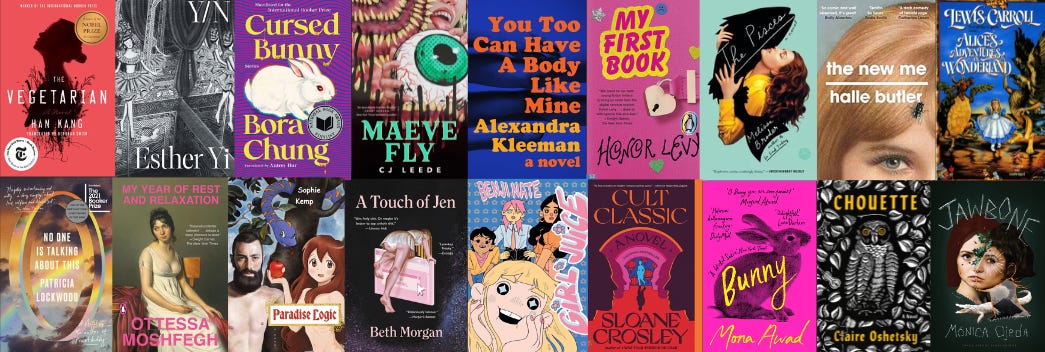

Unhinged Weird Girls: “The New New Weird”

- No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

- Paradise Logic by Sophie Kemp

- A Touch of Jen by Beth Morgan

- Girl Juice by Benji Nate

- Cult Classic by Sloan Crosley

- Biography of X by Catherine Lacey

- Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado

- Bunny by Mona Awad

- My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh

- Chouette by Claire Oshetsky

- Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

- The Vegetarian by Han Kang

- Y/N by Esther Yi

- Jawbone by Monica Ojeda

- Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung

- Maeve Fly by CJ Leede

- You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine by Alexandra Kleeman

- My First Book by Honor Levy

- The Pisces by Melissa Broder

- The New Me by Halle Butler

My Favorite Weirds (that haven’t already been mentioned)

- Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- Open Throat by Henry Hoke

- The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Sheehan Karuntilaka

- Be Kind, My Neighbor by Yugo Limbo

- Horrorstor by Grady Hendrix

- Orange World & Other Stories by Karen Russell

- Devil House by John Darnielle

- The Hike by Drew Magarry

- Crash by J.G. Ballard

- Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu

- Lakewood by Megan Giddings

- Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith

- Uzumaki by Junji Ito

- Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

My TBR Weird

- You Dreamed of Empires by Alvaro Enrique

- Solenoid by Mircea Cărtărescu

- The People of Paper by Salvador Plascencia

- Ultramarine by Mariette Navarro

- Thus Were Their Faces by Silvia Ocampo

- Uranians: Stories by Theodore McCombs

- I Gave You Eyes and You Looked Toward Darkness by Irene Sola

- The Doll’s Alphabet by Camilla Grudova

- Putty Pygmalion by Lonnie Garcia

- Walking Practice by Dolki Min

- One or Two by H.D. Everett

- The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Sterne

- The Library at Mount Char by Scott Hawkins

- State of Paradise by Laura van den Berg

- Treasure Island!!! By Sara Levine

This post was originally published on my Substack.

Leave a comment