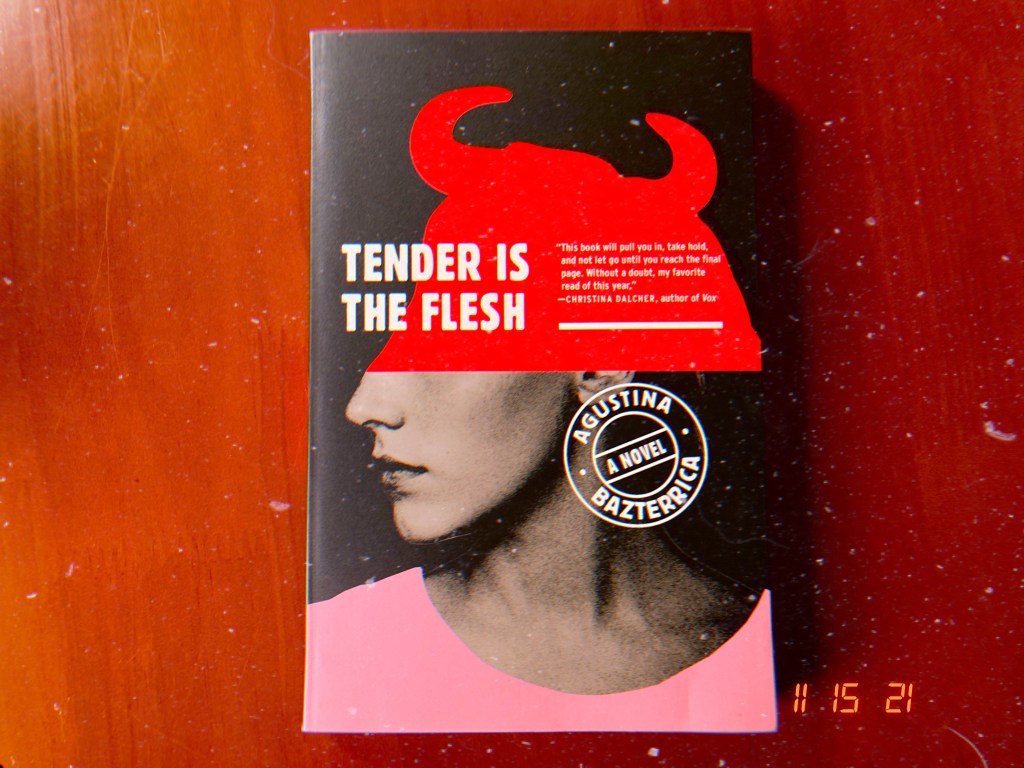

When I first heard about Tender is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica, I was too scared to read it. I’d heard about this disturbing book through the horror lit grapevine and actually picked it up at my favorite horror bookstore (Bucket O Blood!) twice before putting it back. Tender is the Flesh by prominent Buenos Aires author Agustina Bazterrica was originally published as Cadáver Exquisito and was translated by Sarah Moses. Set in the dystopian world where animals are infected by a virus, people must resort to cannibalism to survive. The novel follows Marcos, a man who inherited the slaughterhouse from his father. Marcos is also grieving the loss of his infant son who died from SIDS, while his wife fled to her mother’s house to cope with her own grief. When one of the humans marked for slaughter ends up at Marcos’ home, he begins to care for the woman.

Obviously the parallels between the animal product industry are unavoidable, but the message was conveyed through the emotional response of the reader, not overloading the brutality in the language itself. Knowing the premise of the book beforehand, I was surprised at how the novel was not overly-moralizing. A large portion of the beginning of the novel is spent following Marcos through a typical day on the slaughterhouse floor, walking new recruits past the killings. We (the readers) draw our own conclusions from this, identifying with both the recruit who feels sick and the recruit who is secretly recording. Moreover, I found the rhetoric of the killings more interesting than the brutality described. The humans who are slaughtered are not referred to as “human”— rather “heads,” “product” or “meat.” Their vocal cords are cut out because “meat doesn’t talk.” Completely divorcing language from the slaughtered reduces their humanity almost as much as the brutal disrespect on their physical selves.

Like any good speculative fiction novel, the world building is unparalleled. Halfway through the novel, Marcos visits his sister who she admonishes him for not bringing an umbrella to shield from birds (carriers of the virus). Marcos also walks through the abandoned zoo and even plays with several stray dogs. He seems pretty cavalier about this whole virus thing. In fact, he asserts several times that the virus is just a government conspiracy to eradicate poverty and uphold a caste system, but is it true? The government certainly has been profiting from the virus, but I’m weary of conspiracies these days. This ambiguity was the most interesting part of the novel. I wanted more on the politics and socio-economics of the virus, but we don’t get that because our main character is a rich person. Following someone who worked at the factory might’ve made for a more interesting commentary on the capitalism of the meat industry.

From the first few chapters, Tender is the Flesh reminded me a lot of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep by Philip K. Dick. Themes of empathy and what it means to be human appear frequently in both novels. In Bazterrica’s novel, the “heads” are purposely othered in order to reduce their humanity, get people excited about eating them, and turn a profit. In a different context, the “heads” are almost indistinguishable from humans, similar to the human/android relationship in Do Androids Dream. There is also a romantic plot to both books, where the main character falls for the “othered” human. Thus, both the humanity of the “other” and of the main character are questioned throughout, evoking the question “what’s the different between these two? Are they really so different?”

Even though I knew what I was getting in for, the graphic depictions of the slaughterhouse in this book still disturbed me. I’m not a vegetarian or a vegan, but the theme of the book about ethical consumption worked on me. I can’t say that I will consciously incorporate any lifestyle changes due to this book, but I would not be surprised if it happens naturally. Tender is the Flesh sticks in your craw. Bazterrica should be applauded for her ability to create an emotional response in a wide variety of readers across the world.

Leave a comment